Did Neandertals and modern humans interbreed?

Tue, Oct 27 2009 11:36 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

Ever since William King proposed the taxonomic designation Homo neanderthalensis in 1864, there has been intense debate as to whether Neandertals represent a distinct species from us. Species, as defined by the biological species concept, are populations of organisms that can potentially interbreed and have fertile offspring. It is believed that the lineage leading to Neandertals and modern humans split sometime around 500,000 years ago. For most of their existence Neandertals and early modern humans were geographically isolated (and by extension reproductively isolated) from one another. The big question is whether they could have produced viable offspring when they met.

Today, most researchers acknowledge that some sexual encounters could have occurred between Neandertals and modern humans. The more interesting question is how common were these encounters and did they leave their mark on the modern gene pool. Undoubtedly, modern humans and Neandertals would have recognised each other as fellow humans but this does not mean that they would have acted humanely to each another. Countless social and psychological studies have shown humans to have a very strong "us versus them" mentality, that no doubt also existed in our ancestors. It is unlikely that modern humans and Neandertals had an easy relationship. Most sexual encounters that took place between the two were likely opportunistic and probably involved enslavement and rape.

The morphological evidence

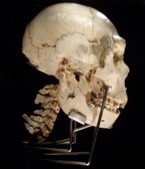

Palaeoanthropologists generally have little problem seperating Neandertals and modern humans based on their gross morphologies. However, some of the earliest modern humans from central Europe have traits that have been seen as evidence for continuity between them and Neandertals. These fossils, particularly those from Peştera cu Oase in Romania and Mladeč in the Czech Republic, have been touted as exemplars for modern-Neandertal admixture. These specimens show traits that are seen in high frequencies in Neandertals, such as bunning of the occipital and the presence of a suprainiac fossa.

However, many researchers have questioned whether these traits are in fact distinctly Neandertal. For instance, the form of the occipital seems to be different in early Upper Palaeolithic populations, leading many to favour the term hemibun to describe the shape of the occipital in early Europeans. Lieberman and colleagues has gone as far as to suggest that the buns seen in these two groups are not homologous. Similarly, it has been argued that the shape of the suprainiac fossa is distinct in early modern Europeans compared to Neandertals.

A palpable difficulty in assessing proposed Neandertal traits in early modern humans is that both groups shared similar niches and some traits may be the result of lifetime behavioural adaptations or convergent evolution. Indeed, the shared robustness of these early humans is likely due to the higher physical activities of these Late Pleistocene groups than during later period.

The genetic evidence

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has some characteristics that make it ideal for analyses of ancient specimens. MtDNA is found in abundance – cells can have thousands of copies of mtDNA, while only containing two copies of nuclear DNA. Moreover, its structure and location within the cell make it more resistant to decay. All the studies of Neandertal mtDNA to date cluster outside the range for modern human mtDNA variation. However, the mitochondria contain only a small part of the total DNA that make up a genome. The possibility that Neandertal genes could show up somewhere else in the genome cannot be ruled out.

The recent announcement by Svante Pääbo that he is sure that Neandertals and modern humans had sex is quite a bold pronouncement coming from a scientist. It raises the question of whether this ascertain is based on some hard evidence they found while sequencing the Neandertal genome. It is possible that if there was some Neandertal genes passed on to the first moderns in Europe, they could have got eliminated from the subsequent gene pool as population sizes fluctuated during the more severe climatic episodes. A more likely scenario is that Pääbo's team found evidence of modern introgression in the Neandertal genome. In all likelihood the incoming modern humans were more numerous than the Neandertals, thereby absorbing the endemic populations through genetic swamping.

References

Caspari RE. 1991. The evolution of the posterior cranial vault in the central European Upper Pleistocene. PhD dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

King, W., 1864. The reputed fossil man of Neanderthal. Quarterly Journal of Science 1, 88–97.

Krings et al. 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell vol. 90 (1) pp. 19-30.

Krings M, Capelli C, Tschentscher F, et al. 2000. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nat Genet 26, 144–146.

Lieberman et al. 2000. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. Evol. vol. 38 (2) pp. 291-315.

Nara MT. 1994. Etude de la variabilité de certainscaractères métriques et morphologiques des Néandertaliens. Bordeaux: Thèse de Docteur.

Pääbo S, Poinar H, Serre D, et al. 2004. Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Ann Rev Genet 38, 645–679.

Above photos modified from originals by erix! and fangleman under creative commons license.

Today, most researchers acknowledge that some sexual encounters could have occurred between Neandertals and modern humans. The more interesting question is how common were these encounters and did they leave their mark on the modern gene pool. Undoubtedly, modern humans and Neandertals would have recognised each other as fellow humans but this does not mean that they would have acted humanely to each another. Countless social and psychological studies have shown humans to have a very strong "us versus them" mentality, that no doubt also existed in our ancestors. It is unlikely that modern humans and Neandertals had an easy relationship. Most sexual encounters that took place between the two were likely opportunistic and probably involved enslavement and rape.

The morphological evidence

Palaeoanthropologists generally have little problem seperating Neandertals and modern humans based on their gross morphologies. However, some of the earliest modern humans from central Europe have traits that have been seen as evidence for continuity between them and Neandertals. These fossils, particularly those from Peştera cu Oase in Romania and Mladeč in the Czech Republic, have been touted as exemplars for modern-Neandertal admixture. These specimens show traits that are seen in high frequencies in Neandertals, such as bunning of the occipital and the presence of a suprainiac fossa.

However, many researchers have questioned whether these traits are in fact distinctly Neandertal. For instance, the form of the occipital seems to be different in early Upper Palaeolithic populations, leading many to favour the term hemibun to describe the shape of the occipital in early Europeans. Lieberman and colleagues has gone as far as to suggest that the buns seen in these two groups are not homologous. Similarly, it has been argued that the shape of the suprainiac fossa is distinct in early modern Europeans compared to Neandertals.

A palpable difficulty in assessing proposed Neandertal traits in early modern humans is that both groups shared similar niches and some traits may be the result of lifetime behavioural adaptations or convergent evolution. Indeed, the shared robustness of these early humans is likely due to the higher physical activities of these Late Pleistocene groups than during later period.

The genetic evidence

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has some characteristics that make it ideal for analyses of ancient specimens. MtDNA is found in abundance – cells can have thousands of copies of mtDNA, while only containing two copies of nuclear DNA. Moreover, its structure and location within the cell make it more resistant to decay. All the studies of Neandertal mtDNA to date cluster outside the range for modern human mtDNA variation. However, the mitochondria contain only a small part of the total DNA that make up a genome. The possibility that Neandertal genes could show up somewhere else in the genome cannot be ruled out.

The recent announcement by Svante Pääbo that he is sure that Neandertals and modern humans had sex is quite a bold pronouncement coming from a scientist. It raises the question of whether this ascertain is based on some hard evidence they found while sequencing the Neandertal genome. It is possible that if there was some Neandertal genes passed on to the first moderns in Europe, they could have got eliminated from the subsequent gene pool as population sizes fluctuated during the more severe climatic episodes. A more likely scenario is that Pääbo's team found evidence of modern introgression in the Neandertal genome. In all likelihood the incoming modern humans were more numerous than the Neandertals, thereby absorbing the endemic populations through genetic swamping.

References

Caspari RE. 1991. The evolution of the posterior cranial vault in the central European Upper Pleistocene. PhD dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

King, W., 1864. The reputed fossil man of Neanderthal. Quarterly Journal of Science 1, 88–97.

Krings et al. 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell vol. 90 (1) pp. 19-30.

Krings M, Capelli C, Tschentscher F, et al. 2000. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nat Genet 26, 144–146.

Lieberman et al. 2000. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. Evol. vol. 38 (2) pp. 291-315.

Nara MT. 1994. Etude de la variabilité de certainscaractères métriques et morphologiques des Néandertaliens. Bordeaux: Thèse de Docteur.

Pääbo S, Poinar H, Serre D, et al. 2004. Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Ann Rev Genet 38, 645–679.

Above photos modified from originals by erix! and fangleman under creative commons license.

View Comments

John Hawks on Ardipithecus

Razib Khan of the Gene Expression blog interviews John Hawks regarding the significance of Ardipithecus ramidus.

Homo heidelbergensis and the muddle in the middle

Sat, Oct 10 2009 11:45 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

At the conference, much attention was focused on the Middle Pleistocene "muddle in the middle" [3], particularly the role of Homo heidelbergensis in hominin evolution. While H. heidelbergensis possesses both archaic and derived traits intermediate between H. erectus and later members of the Homo genus, it lacks uniquely derived traits or autapomorphies, which are a prerequisite for defining a species.

H. heidelbergensis has traits that have been interpreted as nascent Neandertal autapomorphies, leading some researchers to propose that there was a continuous evolution of Neandertals [4-6]. This accretion model would make H. heidelbergensis a chronospecies on the continuum of the Neandertal lineage, a view championed by Jean-Jacques Hublin. The accretion model proposes that Neandertals evolved by anagenesis, i.e. non-branching evolutionary change.

Another scenario views both the European and African H. heidelbergensis as a single species, and the last common ancestor of both Neandertals and modern humans. Alternatively, H. heidelbergensis could have become isolated in Europe and evolved into Neandertals, while the African populations led to modern humans.

During the conference, Ian Tattersall noted that while the accretion model explains some of the variation in the Middle Pleistocene, it cannot account for some outliers, such as the 28 or so specimens that have been recovered from the Sima de los Huesos in Atapuerca, Spain. Tattersall is not the first author to call the accretion model into question [7]. Recent dates have placed the Sima fossils at just over half-a-million years old. Based on the dissimilarity between these fossils and the penicontemporaneous H. heidelbergensis from the rest of Europe, Tattersall proposes that two hominin lineages coexisted in Europe before the arrival of H. sapiens. He suggests that one line (which may include the Sima specimens) led to the Neandertals, while the branch which included H. heidelbergensis went extinct. If Tattersall is correct it would mean that the Sima fossils, which are currently classified as H. heidelbergensis, must be designated another name.

Hublin is to his guns and doesn't see any need to reclassify the Sima material. He goes as far as to suggest binning the species name H. heidelbergensis altogether and instead reassigning all these Middle Pleistocene fossils as H. neanderthalensis. Whatever the outcome is in this debate, it appears that hominin evolution in the Middle Pleistocene is more complex than we have previously suspected.

References

1. Balter M. New work may complicate history of Neandertals and H. sapiens. Science 2009; 326:224-5.

2. Darwin C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. New York, A. L. Burt; 1874.

3. Butzer KW, Isaac GL, International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences 9C1. After the Australopithecines : stratigraphy, ecology, and culture, change in the Middle Pleistocene . The Hague : Mouton ; Chicago : distributed in the USA and Canada by Aldine; 1976.

4. Hublin. Paleogeography, and the evolution of the Neandertals. In: Akazawa, Aoki, Bar-Yosef, Eds. Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:295-310.

5. Hublin. Climatic Changes, Paleogeography, and the Evolution of the Neandertals. In: Akazawa, Aoki, Bar-Yosef, Eds. Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:295-310.

6. Martinón-Torres M, Bastir M, Bermúdez de Castro JM, Gómez A, Sarmiento S, Muela A, Arsuaga JL. Hominin lower second premolar morphology: evolutionary inferences through geometric morphometric analysis. J Hum Evol 2006; 50:523-33.

7. Hawks JD, Wolpoff MH. The accretion model of Neandertal evolution. Evolution 2001; 55:1474-85.

The pelvis of Ardipithecus ramidus

Fri, Oct 2 2009 06:04 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

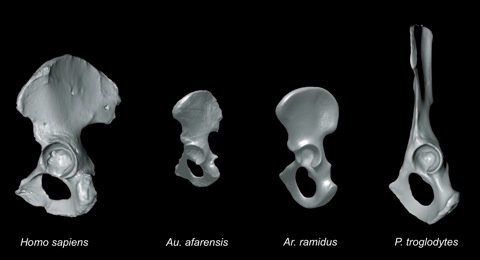

One of the anatomical features that sets humans apart from other living primates is the shape of our pelvis. The shift from a quadrupedal aboreal lifestyle to habitually walking on two legs requires a substantial reconfiguration of the hip region. The 4.4 million year old Ardipithecus ramidus fossil remains give us a glimpse of what the one of the earliest members of the hominin lineage looked like. While the feet of Ar. ramidus show that it was still adapted to life in the trees, the pelvis shows significant adaptations to walking upright on two legs.

The gluteus maximus, which is a relatively minor muscle in quadrupeds has been reconfigured into the largest muscle in humans, in order to stabilize the pelvis and trunk in an upright position. The derived nature of the ilium of Ar. ramidus suggests that the enlargement of the gluteal maximus had already begun. The craniocaudal height of the pelvis is also reduced, which would have lowered the relatively long trunk's centre of mass. This would have allowed for more stable bipedal locomotion.

However, the ischium is quite primitive compared to the ilia, likely to accommodate the large hindlimb musculature required for tree climbing. The two best preserved australopithicine pelves, AL 288-1 and Sts 14, both have short ischia, like those seen in modern humans. The preserved portion of the ischial ramus in Ar. ramidus is significantly larger than that found in any of the Australopithecines. A long ischium creates a greater moment arm suggesting that Ar. ramidus had relatively powerful hamstrings, a trait that is common in tree-dwelling primates.

The configuration of the ARA-VP-6/500 pelvis suggests that lower lumbars were probably posteriorly positioned, allowing for lordosis of the spine. A reduction in iliac height would have further facilitated lordosis. Lordosis positions the spine to a more forward position, so that it directly overlies the hips during erect posture. Lower spinal lordosis would have allowed the full extension of the hips and knee during extended bipedal locomotion.

Ar. ramidus was quite capable of bipedal locomotion, as attested to by the morphology of its pelvis and foot. However, its large thigh muscles and its prehensile big toe show that it was still very much adapted to arboreal life. Ar. ramidus shares arboreal adaptations that were probably present in the human-chimp last common ancestor, as well as bipedal adaptations that are so characteristic of hominins. Ar. ramidus appears to have been an arboreal ape with bipedal adaptations, rather than a biped with arboreal adaptations. It is not until almost half-a-million years later, with the arrival of Australopithecus afarensis, that we find a truly habitual bipedal hominin.

Four Stone Hearth #75

Wed, Sep 9 2009 04:55 | Anthropology | Permalink

Welcome to Four Stone Hearth number 75. Four Stone Hearth is a fortnightly anthropology blog carnival. Topics covered span the four major fields of anthropology: archaeology, socio-cultural anthropology, bio-physical anthropology and linguistic anthropology. If you would like to host the carnival, please write to . The next issue will be hosted at the Afarensis blog on 23 September. So without further preamble, let's get on with the show.

Archaeology

Martin Rundkvist talks about his experience digging at a Middle Neolithic coastal site in Sweden. Among the finds were small potsherds and a fine example of Pitted Ware.

A recent article in the journal Nature reports on the "oldest handaxes" in Europe. John Hawks gives his interpretation regarding the significance of these bifaces, suggesting that although Lower Pleistocene hominins had the technology to produce bifacial handaxes, they were not a necessity.

Biological anthropology

Anybody who has been following anthropology news for the past few weeks will be well aware of the spirited reaction that a recent editorial in Scientific American generated. The article calls for the adoption of more open practices with regard to accessing human fossils. I have written a piece where I give my own take on the issue.

Matthew Wolf-Meyer reviews Jonathan Marks' latest book "Why I am not a scientist". Jonathan Marks is a controversial anthropologist, who sticks to his guns in this, his latest work. Ever thought provoking, Marks is bound to stir up some debate among anthropologists and scientists alike.

There has been a lot of debate regarding whether Central European farmers were the descendants of indigenous hunter-gathers or the result of a demic diffusion from the southeast. Dienkes reports on a new study which suggests that Central European farmers were in fact probably not descended from local hunter-gatherer groups.

Stephen Wang asks the age old question of how similar Neandertals were to us and how they thought about the world.

Linguistic anthropology

The Innovation in Teaching blog explains the concept of a “focused gathering”, a term coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. The post goes on to discuss how this concept helps us better think about classroom dynamics.

Socio-cultural anthropology

Over at Neuroanthropology, Daniel Lende has a revealing piece which looks at food crises in Lesotho and the role funerals play in coping with these food shortages. In another post Daniel takes on the recent "research" by researchers Ogi Ogas and Sai Gaddam, which is plagued by poor methodologies and a pseudoscientific approach to neuroscience. Greg Downey follows this up with his own take on some of the methodological flaws of the investigators, principally their inflexibility in the face of contradictory evidence.

Rex over at the Savage Minds blog suggests that the real question anthropologists should ask regarding internet addiction is not whether it exists but rather "how and in what forms do preexisting cultural structures predispose people to think something is true?"

Greg Laden debunks the fallacy that culture overrides biology. This part of a larger series on the common misperceptions that people have regarding biology.

Idris Mootee thinks that industrial designers need to think like cultural anthropologists. He uses the example of how different cultures adopt their own particular posture while sitting. By being aware of this, designers can better accommodate the needs of the end user. Joana Breidenbach of the Culture Matters blog is of a similar opinion:

"Design thinking has many overlaps with the anthropological approach, such as starting out with as little preconceived ideas about the research topic as possible and gaining an empathetic understanding through immersion during fieldwork."

Lian explores the the archaeology of the worship of Celtic deities in Roman Britain.

Lorenz at the antropologi blog reviews Thomas Hylland Eriksen's new book "Engaging Anthropology". In it, he addresses the question of why anthropologists fail to engage the general public. In a similar piece that appeared in Times Higher Education, anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes asserts that part of the problem may lie with universities:

"Scholars who want to reach diverse publics - through popular writing, speaking or participating in social activism - are not only under-rewarded by their universities, they are often penalised for 'dumbing down' anthropological thinking, cutting social theory into 'soundbites', 'vulgarising' anthropology, sacrificing academic standards or (in the US) for playing to the anti-intellectual, illiberal American popular classes."

Anna Barros shows how trends are subject to selection. She demonstrates how memes can be transmitted from person to person and how they respond to selection pressures.

One more thing…

Each of the four fields of anthropology can offer us a glimpse into our past. Perhaps more importantly, they can take us on a journey and show us the steps which got us to where we are today. Photography offers yet another way of archiving the past. To use the clichéd metaphor – photographs are moments frozen in time. A Flickr photostream by Jason Powell wonderfully bridges the gap between the past and the present, through the medium of photography. Enjoy!

Fossil and data access in palaeoanthropology

Tue, Sep 8 2009 01:50 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

A recent article in Scientific American has generated a lot of buzz in the anthropology blogosphere. The piece discusses the problems of accessing human fossil remains, reopening the discussion on how open anthropology needs to be. The reason why data acquisition is such a problem in palaeoanthropology is captured in the opening sentence of an article Stephen Jay Gould and David Pilbeam wrote for Science:

Whenever supply cannot keep up with demand, you can be sure that problems will follow. (Many parents have learned this to their chagrin, when they find out that the Christmas toy du jour, their beloved child so wanted, is sold out.) Each newly unearthed fragment of human bone represents yet another valuable piece in the ever-growing jigsaw puzzle that is our evolutionary history. The study of primary data is of prime importance in paleoanthropology. As a result, a conflict arises, due to the need to study fossils and the limited access placed upon them. Restricted access occurs for a number of reasons, ranging from valid concerns over the fragility of a particular specimen, to scientists reaping the benefits of a research monopoly.

There is an unwritten rule in palaeoanthropology that the discoverers of a fossil have the exclusive rights to publish the initial monograph describing their specimen. Palaeoarchaeologists invest a lot of resources, time and effort in recovering fossils. They will often literally risk body and limb. Dehydration, food poisoning, snake bites, diseases and infections are but some of the hazards field archaeologists face. When they are not digging they are often engaged in the unenviable task of writing grants for their projects. It is understandable that they are wary of outsiders who expect free access to their hard-won prizes.

Ancient fossils usually come out of the ground highly fragmented and in a poor state of preservation. Much time is required to clean, preserve and reconstruct them before conducting a phylogenetic analysis. While many people have focused on the fact that certain specimens have taken an exhorbitant amount of time to describe, thus holding up the process of peer validation, it must also be kept in mind that these represent only a small fraction of the total human fossil record. While it of the utmost importance to make fossils available to outside investigators in a timely fashion, it is perhaps not the most fruitful or constructive area in which to be directing our attention.

Conflicts arise between researchers who want to access fossil material and curators who are genuinely concerned about the wear and tear that these fossils have endured through repeated handling. Curators will often direct researchers to others who have already measured the material in question, to avoid the redundant repetition of measurements. It is often at this point that researchers can come up against a brick wall, with peers who are unwilling to relinquish their valued data. Like the fossils themselves, unique data is a precious commodity and alas is necessary for publication. For good or for ill, peer-reviewed publications are placed in high regard in the anthropological world. Its role when it comes to job-seeking or tenure cannot be underestimated. An incredible amount of data has been collected through the years on ancient human remains but they are rarely put in the public domain. A noteworthy exception is the data on some 3,000 skulls from 17 worldwide populations, measured and made freely available by the eminent anthropologist William W. Howells (pdf file). The Howells' dataset is perhaps that man's most lasting legacy, at least in the sheer number of times his data have been used and referenced. Similarly, we need to place great value on other researchers who make their data available and this should be taken into consideration in matters of career advancement. At a minimum, the sharing of data should be deemed equivalent to research publication.

Positive steps have been taken in the ensure more data is made available. The US National Science Foundation encourage applicants to make provisions to make data available after the research has been completed. The NSF states that:

Anthropologists who fail to comply with these recommendations may have subsequent grant proposals turned down on these grounds. There is an ever-growing number of high quality casts and 3D images of fossils becoming available. Taphonomic processes may deform the fossilised bone and filling in gaps has often required a liberal amount of guesswork. 3D images often allow for better reconstructions of the original specimens, due to the ability to interpolate absent regions and more readily pinpoint and correct deformation. Research centres have woken up to the fact that collaborative projects tend to have a greater synergy due to their symbiotic nature. For palaeoanthropology to become a truly open discipline, it will not only need researchers to be more freehanded with their data, but will require funding agencies, universities and research centres to incentivise such actions.

Related reading

Fossil access editorial @ John Hawks weblog.

Science Suffers From The Idiots At Scientific American @ Anthropology.net.

Take your time @ A Primate of Modern Aspect.

Delson et al. Databases, data access, and data sharing in paleoanthropology: First steps. Evol. Anthropol. (2007) vol. 16 (5).

Gibbons. Glasnost for Hominids: Seeking Access to Fossils. Science (2002) vol. 297 pp. 1464-1468.

Mafart. Human fossils and paleoanthropologists: a complex relation. Journal of Anthropological Sciences (2008) vol. 86 pp. 201-204.

Pilbeam and Gould. Size and Scaling in Human Evolution. Science (1974) vol. 186 ( 4167), 892-901.

Tattersall and Schwartz. Is paleoanthropology science? Naming new fossils and control of access to them. Anat Rec (2002) vol. 269 (6) pp. 239-41.

"Human paleontology shares a peculiar trait with such disparate subjects as theology and extraterrestrial biology: it contains more practitioners than objects for study."

– Stephan J. Gould and David Pilbeam

Whenever supply cannot keep up with demand, you can be sure that problems will follow. (Many parents have learned this to their chagrin, when they find out that the Christmas toy du jour, their beloved child so wanted, is sold out.) Each newly unearthed fragment of human bone represents yet another valuable piece in the ever-growing jigsaw puzzle that is our evolutionary history. The study of primary data is of prime importance in paleoanthropology. As a result, a conflict arises, due to the need to study fossils and the limited access placed upon them. Restricted access occurs for a number of reasons, ranging from valid concerns over the fragility of a particular specimen, to scientists reaping the benefits of a research monopoly.

There is an unwritten rule in palaeoanthropology that the discoverers of a fossil have the exclusive rights to publish the initial monograph describing their specimen. Palaeoarchaeologists invest a lot of resources, time and effort in recovering fossils. They will often literally risk body and limb. Dehydration, food poisoning, snake bites, diseases and infections are but some of the hazards field archaeologists face. When they are not digging they are often engaged in the unenviable task of writing grants for their projects. It is understandable that they are wary of outsiders who expect free access to their hard-won prizes.

Ancient fossils usually come out of the ground highly fragmented and in a poor state of preservation. Much time is required to clean, preserve and reconstruct them before conducting a phylogenetic analysis. While many people have focused on the fact that certain specimens have taken an exhorbitant amount of time to describe, thus holding up the process of peer validation, it must also be kept in mind that these represent only a small fraction of the total human fossil record. While it of the utmost importance to make fossils available to outside investigators in a timely fashion, it is perhaps not the most fruitful or constructive area in which to be directing our attention.

Conflicts arise between researchers who want to access fossil material and curators who are genuinely concerned about the wear and tear that these fossils have endured through repeated handling. Curators will often direct researchers to others who have already measured the material in question, to avoid the redundant repetition of measurements. It is often at this point that researchers can come up against a brick wall, with peers who are unwilling to relinquish their valued data. Like the fossils themselves, unique data is a precious commodity and alas is necessary for publication. For good or for ill, peer-reviewed publications are placed in high regard in the anthropological world. Its role when it comes to job-seeking or tenure cannot be underestimated. An incredible amount of data has been collected through the years on ancient human remains but they are rarely put in the public domain. A noteworthy exception is the data on some 3,000 skulls from 17 worldwide populations, measured and made freely available by the eminent anthropologist William W. Howells (pdf file). The Howells' dataset is perhaps that man's most lasting legacy, at least in the sheer number of times his data have been used and referenced. Similarly, we need to place great value on other researchers who make their data available and this should be taken into consideration in matters of career advancement. At a minimum, the sharing of data should be deemed equivalent to research publication.

Positive steps have been taken in the ensure more data is made available. The US National Science Foundation encourage applicants to make provisions to make data available after the research has been completed. The NSF states that:

It expects investigators to share with other researchers, at no more than incremental cost and within a reasonable time, the data, samples, physical collections and other supporting materials created or gathered in the course of the work.

Anthropologists who fail to comply with these recommendations may have subsequent grant proposals turned down on these grounds. There is an ever-growing number of high quality casts and 3D images of fossils becoming available. Taphonomic processes may deform the fossilised bone and filling in gaps has often required a liberal amount of guesswork. 3D images often allow for better reconstructions of the original specimens, due to the ability to interpolate absent regions and more readily pinpoint and correct deformation. Research centres have woken up to the fact that collaborative projects tend to have a greater synergy due to their symbiotic nature. For palaeoanthropology to become a truly open discipline, it will not only need researchers to be more freehanded with their data, but will require funding agencies, universities and research centres to incentivise such actions.

Related reading

Fossil access editorial @ John Hawks weblog.

Science Suffers From The Idiots At Scientific American @ Anthropology.net.

Take your time @ A Primate of Modern Aspect.

Delson et al. Databases, data access, and data sharing in paleoanthropology: First steps. Evol. Anthropol. (2007) vol. 16 (5).

Gibbons. Glasnost for Hominids: Seeking Access to Fossils. Science (2002) vol. 297 pp. 1464-1468.

Mafart. Human fossils and paleoanthropologists: a complex relation. Journal of Anthropological Sciences (2008) vol. 86 pp. 201-204.

Pilbeam and Gould. Size and Scaling in Human Evolution. Science (1974) vol. 186 ( 4167), 892-901.

Tattersall and Schwartz. Is paleoanthropology science? Naming new fossils and control of access to them. Anat Rec (2002) vol. 269 (6) pp. 239-41.

Above photo by Simon Strandgaard under creative commons license.

Anthro blog carnival: Four Stone Hearth 74

Thu, Aug 27 2009 03:11 | Anthropology | Permalink

The 74th Four Stone Hearth anthropology blog carnival is available over at Adam Henne’s Natures/Cultures blog. Catch up on the latest on anthropology blogging. The next Four Stone Hearth will be hosted here on the 9th of September. Send any anthropology submission for the upcoming carnival to or (be sure to replace [AT] with @ in the email addresses).

Upper Palaeolithic Italy

Sun, Aug 23 2009 05:21 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

Extrapolating from data by Bocquet-Appel et al. (2005) it is possible that the population of Italy did not exceed 1,000 inhabitants. While this figure is little more than a best guess, it still gives us an idea of the fragile nature of these groups, who were living constantly on the edge of extinction. With such small numbers inbreeding can become a serious problem. However, studies of European Upper Palaeolithic people find them to be surprisingly homogenous as a whole, which would suggest a significant amount of gene flow between far-flung populations (Henke 1989, 1991). In order to understand how mating systems would have operated during the Early Upper Palaeolithic researchers have looked to modern hunter-gatherer groups. Such studies have found hunter-gatherers to have less group closure than agriculturalists. This would have been an important survival strategy for the hunter-gatherer groups of the Upper Palaeolithic, especially when faced with unpredictable environmental conditions and already constrained mating networks. This open network is also reflected in the material culture from this period. Venus figurines, dating chiefly from the Gravettian period, have been found over an area of approximately 2000 km, spanning from modern day Russia in the Northeast to Spain in the Southwest. The Italian Venuses from Savignano, Balzi Rossi and Parabita show the same female form, with an enlarged midsection, pronounced buttocks, large breasts and voluminous thighs, characteristic of the vast majority of these figurines. This suggests that there was an extensive flow of people and ideas during the Early Upper Palaeolithic. This is further supported by the transport of exotic materials, such as flint and shells over distances of several hundred kilometres.

At around 29,000 years ago, the Italian archaeological record falls silent. This hiatus seems to last for around two millennia. Mussi (2000) suggests that Italy may have become a "demographic trap", due to the combination of low population numbers and small group sizes, leading to the eventual extinction of the Aurignacian people.

Based on their assemblages, is believed that the Gravettian people were a new group, who likely entered the Italian peninsula from south-eastern France. As climatic conditions worsen, more exotic artefacts begin to appear in the archaeological record. A major concentration of sites date to around 25,000 BP, suggesting the arrival of immigrants from northern Europe coinciding with the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum. As new people entered Italy, they had to adapt to strange environments and a more limited variety of animals. We no longer find high altitude sites like in the Aurignacian. This shift to lower altitudes is undoubtedly due to the advancing ice. There is evidence of decreased mobility during the Last Glacial Maximum, which continues until the Mesolithic period (Holt 2003). This may reflect a move to more closed systems, as regionalisation grew due to the ever-increasing population density and greater competition over territories. The burial practices, art, and personal adornments of the Early Upper Palaeolithic, which paralleled those from the rest of the continent disappear at the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, further reflecting a shift to more closed social networks. As temperatures begin to improve towards the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, these cultural artefacts reappear in abundance, once again mirroring the styles and practices seen elsewhere in Europe.

Sicily comes in for special attention. The island has long been of interest to anthropologists, who saw the it as a stepping stone between North Africa and Europe. Ferembach (1986) postulated that Sicily may have served as an entry point for the North African Aterians (or their ancestors) around 50,000 years ago, who later became the "Cro-Magnon race". However, this idea finds little archaeological or skeletal support. Evidence of occupation prior to the Last Glacial Maximum in Sicily is patchy at best. At the site of Fontana Nuova, Aurignacian tools and isolated fragments of human bone have been found and estimated to date to around 30,000 years ago, making it the earliest record of occupation for the island (Chilardi et al 1996). However, it is the only evidence we have for the colonisation of the island during the Aurignacian and it is not until the Epigravettian (~20,000-10,000 BP) that we have further evidence of humans in Sicily. This suggests that the earliest settlers probably went extinct due their small numbers, limited resources and restricted gene flow with the mainland. It also reflects the pattern seen in the rest of Italy, since there are no Aurignacian sites known after 30,000 BP.

At the site of Grotta di San Teodoro the skeletal remains of seven individuals were found, making it the single largest Upper Palaeolithic sample in Sicily. An unpublished direct AMS 14C date situates the skeletal remains at around 14,800 BP (D’Amore et al. 2009). A recent craniometric study of the San Teodoro skeletons shows that they have higher affinities with the Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic populations, rather than Early Upper Palaeolithic ones (ibid.). These results suggest one of two possible scenarios (a) an early arrival with gene flow, thus explaining the homogeneity with the mainland Italian groups or (b) the late arrival of the direct descendants of the San Teodoro population on the island of Sicily. At the time of the Last Glacial Maximum there was probably a land bridge between Sicily and the Italian mainland, with sea levels being some 120 metres lower. The appearance of exotic faunal evidence further suggest this land connection. While Sicily was occupied as early as the Aurignacian, it may not have been until the Late Epigravettian that the island had a stable population able to overcome the threat of extinction. Like the rest of Italy, Sicily gives us a unique insight the challenges faced by Europe’s latest inhabitants.

*BP is used to indicated uncalibrated radiometric years before present.

References

Bocquet-Appel et al. Estimates of Upper Palaeolithic meta-population size in Europe from archaeological data. Journal of Archaeological Science (2005) vol. 32 (11) pp. 1656-1668.

Chilardi S, Frayer DW, Gioia P, Macchiarelli R, Mussi M (1996) Fontana Nuova di Ragusa (Sicily, Italy): southernmost Aurignacian site in Europe 70: 553-563.

D'Amore G, Marco SD, Tartarelli G, Bigazzi R, Sineo L (2009) Late Pleistocene human evolution in Sicily: comparative morphometric analysis of Grotta di San Teodoro craniofacial remains 56: 537-550.

Ferembach. Les Hommes du Paléolithique Supérieur. Autour du Bassin Méditerraneen. L'Anthropologie (1986) vol. 90 (3) pp. 579-587.

Henke W (1991) Biological Distances in Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Human Populations in Europe. In: Variability and Evolution. Poznan, Poland: Miskiewicz University Press. pp. 39-64.

Henke (1989) Jungpaläolithiker und Mesolithiker: Beiträge zur Anthropologie. Habilitationsschrift, FB Biologie, Mainz, 1701 S.

Holt BM (2003) Mobility in Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Europe: Evidence from the lower limb. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

Mussi (1990) Continuity and change in Italy at the Last Glacial Maximum.. In: Soffer, Gamble, editors. The world at 18000: high latitudes. London: . pp. 126-147.

Mussi M (2000) Heading south: the gravettian colonisation of Italy. In: Roebroeks, Mussi, Svoboda, Fennema, editors. Hunters of the Golden Age: The Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Eurasia 30,000–20,000 BP. Leiden: Leiden University Press. pp. 355-374.

Measuring cranial variation using geography as a proxy for neutral genetic distances

Fri, Aug 14 2009 07:35 | Biological Anthropology | Permalink

Certain anatomical features of the human skeleton are known to vary with geography and climate. To what extent each variable contributes to our physical makeup is less clear. The problem is that populations with similar climate are geographically close to one another. Even if we find shared traits among populations from similar climates it may be just as a result of geographic proximity (and thus clinal gene flow), rather than shared common ancestry.

As I mentioned in my previous post, anthropologists often compared cranial data to matched microsatellite datasets. However, it is rarely possible to get an exact match between the cranial and microsatellite populations. The anthropologist will instead use populations that are genetically similar and which may or may not be representative of the target population. Another option is to substitute microsatellite data with geographic distances, since studies have found a strong correlation between genetic distance and geographic distance (Manica et al. 2005; Ramachandran et al. 2005; Romero et al. 2008). This allows us to get around the need to match phenotypic data with genetic datasets.

A recent paper by Betti et al. used geographic distance as a proxy for neutral genetic distance. They set out to test the extent to which cranial differences can be explained by geographic proximity, by comparing pairwise phenotypic distances among populations and pairwise geographic distances using isolation by distance (IBD) models, as well as comparing pairwise cranial distances with climatic variables after correcting for IBD. Geographic distances were calculated as the shortest distance over land between populations while avoiding areas greater than 2000 metres above sea level. Intercontinental land bridges were also factored into their model.

Their study found geographic distance (and by extension genetic distance) to be a strong predictor of cranial variation. Minimum and maximum temperatures were also a significant predictor of cranial differentiation but not as strong as geographic distance. It also appears that much of this climate-related variation is influenced by the populations from exceptionally cold climates. A previous study by Roseman also found that populations living in extremely cold climates showed greater selection. Betti et al. suggest that this may be due to culture acting as an environmental buffer, with the buffer breaking down at extremely cold climates, after which cranial plasticity takes over.

Since climate and geographic distance covary, not considering isolation by distance leads to an overestimation of the effect of climate on cranial differences between populations. Not surprisingly facial traits showed the strongest correlation with climate. In summary, this study suggests that cranial measurements are predominately influenced by neutral evolutionary processes, especially in populations that do not live in extremely cold climates.

References:

Betti et al. 2009. The relative role of drift and selection in shaping the human skull. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. in press.

Manica A, Prugnolle F, Balloux F. 2005. Geography is a better determinant of human genetic differentiation than ethnicity. Hum Genet 118:366–371.

Ramachandran S, Deshpande O, Roseman CC, Rosenberg NA, Feldman MW, Cavalli-Sforza LL. 2005. Support from the relationship of genetic and geographic distance in human populations for a serial founder effect originating in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15942–15947.

Romero IG, Manica A, Goudet J, Handley LL, Balloux F. 2008. How accurate is the current picture of human genetic variation? Heredity 102:120–126.

Above photo by jacorbett70 under creative commons license.

As I mentioned in my previous post, anthropologists often compared cranial data to matched microsatellite datasets. However, it is rarely possible to get an exact match between the cranial and microsatellite populations. The anthropologist will instead use populations that are genetically similar and which may or may not be representative of the target population. Another option is to substitute microsatellite data with geographic distances, since studies have found a strong correlation between genetic distance and geographic distance (Manica et al. 2005; Ramachandran et al. 2005; Romero et al. 2008). This allows us to get around the need to match phenotypic data with genetic datasets.

A recent paper by Betti et al. used geographic distance as a proxy for neutral genetic distance. They set out to test the extent to which cranial differences can be explained by geographic proximity, by comparing pairwise phenotypic distances among populations and pairwise geographic distances using isolation by distance (IBD) models, as well as comparing pairwise cranial distances with climatic variables after correcting for IBD. Geographic distances were calculated as the shortest distance over land between populations while avoiding areas greater than 2000 metres above sea level. Intercontinental land bridges were also factored into their model.

Their study found geographic distance (and by extension genetic distance) to be a strong predictor of cranial variation. Minimum and maximum temperatures were also a significant predictor of cranial differentiation but not as strong as geographic distance. It also appears that much of this climate-related variation is influenced by the populations from exceptionally cold climates. A previous study by Roseman also found that populations living in extremely cold climates showed greater selection. Betti et al. suggest that this may be due to culture acting as an environmental buffer, with the buffer breaking down at extremely cold climates, after which cranial plasticity takes over.

Since climate and geographic distance covary, not considering isolation by distance leads to an overestimation of the effect of climate on cranial differences between populations. Not surprisingly facial traits showed the strongest correlation with climate. In summary, this study suggests that cranial measurements are predominately influenced by neutral evolutionary processes, especially in populations that do not live in extremely cold climates.

References:

Betti et al. 2009. The relative role of drift and selection in shaping the human skull. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. in press.

Manica A, Prugnolle F, Balloux F. 2005. Geography is a better determinant of human genetic differentiation than ethnicity. Hum Genet 118:366–371.

Ramachandran S, Deshpande O, Roseman CC, Rosenberg NA, Feldman MW, Cavalli-Sforza LL. 2005. Support from the relationship of genetic and geographic distance in human populations for a serial founder effect originating in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15942–15947.

Romero IG, Manica A, Goudet J, Handley LL, Balloux F. 2008. How accurate is the current picture of human genetic variation? Heredity 102:120–126.

Above photo by jacorbett70 under creative commons license.

Examining cranial robusticity

Sat, Aug 8 2009 11:23 | Biological Anthropology | Permalink

Palaeoanthropologist Darren Curnoe (2009) gives the following biological definition of the term ‘robust’:

…a descriptive anatomical term referring to individuals, complexes, organs, structures or traits which are heavily built, rugged, well defined or corpulent.

Bones tend to more robust where muscles, tendons or ligaments insert into the periosteum. When these insertion sites are subjected to stress, blood flow increases. This in turn stimulates the production of osteoblasts, which lay down extra bone. With respect to the skull the term robust is generally used to refer to so-called superstructures, such as the supraorbital ridges, occipital crests or zygomaxillary tuberosities. Anthropologists often classify robusticity based on the relative expression of a particular trait, or indeed its absence. Given that robusticity is related to physical stress, traits tend to be more pronounced in males and in certain populations (e.g. Aboriginal Australians and Fuegians).

The retention of robust features in certain populations, particularly Aboriginal Australians, has been used to support the multiregional hypothesis of human origins (e.g. Wolpoff et al. 2001; Frayer et al., 1993). On the other hand, proponents of a replacement model see robust traits (e.g. in Australian Aboriginal populations) as retained plesiomorphies and argue that these traits cannot be used to show continuity (Lieberman 2000). In response, many multiregionalists have revised their position to suggest that the reduction of the browridge in later Neandertals, such as St Césaire and Vindija, represents a synapomorphy between Neandertals and modern humans, likely due to interbreeding. The underlying assumption here is that these robust traits have a strong genetic component. Furthermore, there is a notable decrease in cranial robusticity from the early Upper Palaeolithic to late Upper Palaeolithic. It has been suggested that this may reflect changes in diet. Transition from hunter-gather to agricultural lifestyle is associated with a reduction in cranial robusticity, although correlation does not necessarily prove causation. However, not all hunter-gather groups are universally more robust than argriculturalists, which might suggest some other factors at play.

A recent in press paper by Baab et al. sets out to examine the possible mechanisms behind robust cranial characters. The null hypothesis in their study is that neutral evolutionary processes (e.g. genetic drift) were responsible for the pattern of cranial robusticity in modern humans - the rejection of which would suggest selection acting on these traits. To test the null hypothesis of neutral evolution of cranial robusticity Mahalonobis D2 distances for robust characters were compared to Ddm distances derived from microsatellite data. Microsatellites are useful in reconstructing evolutionary relationships due to their unusually high mutation rates, which result in largely selectively neutral polymorphisms.

Of the variables examined, only cranial shape was significantly correlated with robusticity, while cranial size, climate and neutral genetic distances were not. This is at odds with an earlier study by Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996) (1996) who found the strongest correlation between cranial robusticity and cranial size. This finding may be due to use of geometric morphometrics by Baab and colleagues, which is better at separating size and shape compared to the linear morphometrics used by Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996).

Cranial robusticity was not correlated with neutral genetic distances, suggesting that neutral evolutionary processes (e.g. genetic drift) were not responsible for the pattern of cranial robusticity in the populations studied. As noted by the authors, this finding could also be explained by a non-perfect match of populations among some of the cranial and molecular samples. In studies such as this one, it is often difficult to find an exact match between the populations from which we derive our cranial and molecular data. In such cases, we are left with the choice of eliminating samples or using another genetically similar population. The authors choose the latter but neither option is ideal and both have their own disadvantages. Unfortunately, the reason for including Upper Palaeolithic and Neolithic samples in this study is never fully explained and the assumption that modern genetic populations are appropriate proxies for such populations is never justified. Setting this aside, the findings of this study caution the use of robust traits in constructing phylogenetic relationships in modern humans.

The strongest correlations were found between cranial robusticity and either cranial or masticatory shape. This lends support to the hypothesis that robusticity is in some part functionally determined. The study also found crania with more prognathic faces, longer skulls, expanded glabellar and occipital regions to be more robust. Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996) noted a similar tendency of longer skulls to have superstructures, while further emphasising their tendency to be associated with narrow skulls and a large palatal region.

While most of the robust variables in this study were areas of muscle insertions, the supraorbital region has a distinct aetiology. While many have interpreted the supraorbital region as an area of stress reinforcement in the skull (the so-called beam model) which is strongly influenced by mastication (Endo 1966, 1970; Russell 1985), there is a strong evidence to suggest that this is not its primary purpose. Supraorbital development begins early in life, suggesting that the supraorbital ridge may be part of the overall craniofacial complex and is likely under genetic control. While the beam model is intuitive, it is unsupported by empirical data. Hylander and colleagues (Hylander et al. 1991a, 1991b, 1992; Hylander and Ravosa 1992) conducted in vivo strain gauge experiments in different primates to assess the amount of strain magnitudes generated during mastication. They found these levels to be low to induce bone deposition in all the species they studied, even when chewing hard food. Moreover, anthropoids do not show a correlation between the browridge and the moment arms of the masticatory muscles, as the beam model would predict (Ravosa 1991). These researchers adopt the model proposed by Moss and Young (1960), which views supraorbital development as the result of placement of the brain and eyes. They postulated that the reduction of the brow ridge in modern humans was related to the expansion of the frontal lobe in our species. In hominins with orbits positioned well in front of the frontal lobes, as in chimpanzees or the erectines, the space between the orbits and the brain case is bridged by a brow ridge. If the supraorbital region is under genetic control, as the research of Hylander and Ravosa suggests, it would be of interest to examine this region in isolation to assess if it correlates with neutral evolutionary processes, particularly in light of a recent paper by Von Cramen-Taubedal which found the shape of the frontal bone to be consistent with neutral genetic expectation.

References

Baab KL, SE Freidline, SL Wang, T Hanson. 2009. Relationship of cranial robusticity to cranial form, geography and climate in Homo sapiens (in press). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

Curnoe D. 2009. Possible causes and significance of cranial robusticity among Pleistocene-Early Holocene Australians. Journal of Archaeological Science (2009) vol. 36 (4): 980-990.

Endo B. 1966. Experimental studies on the mechanical significance of the form of the human facial skeleton. J Faculty Sci Univ Tokyo (Section V, Anthropol) 3:1–106.

Endo B. 1970. Analysis of stress around the orbit due to masseter and temporalis muscles respectively. J Anthropol Soc Nippon 78:251–266.

Frayer DW, MH Wolpoff, AG Thorne, FH Smith, GG Pope. Theories of modern human origins: the paleontological test. American Anthropologist (1993) vol. 95 (1): 14-50.

Hylander WL, Picq PG, Johnson KR. 1991a. Masticatory–stress hypotheses and the supraorbital region of primates. Am J Phys Anthropol 86:1–36.

Hylander WL, Picq PG, Johnson KR. 1991b. Function of the supraorbital region of primates. Arch Oral Biol 36:273– 281.

Hylander WL, Ravosa MJ. 1992. An analysis of the supraorbital region of primates: a morphometric and experimental approach. In: Smith P, Tchernov E,

editors. Structure, function and evolution of teeth. Tel Aviv: Freund Publishing. p 223–255.

Lieberman, DE. (2000) Ontogeny, homology, and phylogeny in the Hominid craniofacial skeleton: the problem of the browridge. In P. O'Higgins and M. Cohn (eds.) Development, Growth and Evolution: implications for the study of hominid skeletal evolution. London: Academic Press, pp. 85-122.

Moss ML, RW Young. 1960. A functional approach to craniology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 18:281-292.

Mirazón Lahr M, RVS Wright. 1996. The question of robusticity and the relationship between cranial size and shape in Homo sapiens. Journal of Human Evolution.

Ravosa MJ. 1991. Interspecific perspective on mechanical and nonmechanical models of primate circumorbital morphology. Am J Phys Anthropol. 86(3):369-96.

Russell MD. 1985. The Supraorbital Torus:" A Most Remarkable Peculiarity". Current Anthropology. vol. 26 (3) pp. 337

Wolpoff MH, J Hawks, DW Frayer, K Hunley. 2001. Modern Human Ancestry at the Peripheries: A Test of the Replacement Theory. Science. vol. 291 (5502):293-297.

Above photo modified from original by Thomas Hawk under creative commons license.

…a descriptive anatomical term referring to individuals, complexes, organs, structures or traits which are heavily built, rugged, well defined or corpulent.

Bones tend to more robust where muscles, tendons or ligaments insert into the periosteum. When these insertion sites are subjected to stress, blood flow increases. This in turn stimulates the production of osteoblasts, which lay down extra bone. With respect to the skull the term robust is generally used to refer to so-called superstructures, such as the supraorbital ridges, occipital crests or zygomaxillary tuberosities. Anthropologists often classify robusticity based on the relative expression of a particular trait, or indeed its absence. Given that robusticity is related to physical stress, traits tend to be more pronounced in males and in certain populations (e.g. Aboriginal Australians and Fuegians).

The retention of robust features in certain populations, particularly Aboriginal Australians, has been used to support the multiregional hypothesis of human origins (e.g. Wolpoff et al. 2001; Frayer et al., 1993). On the other hand, proponents of a replacement model see robust traits (e.g. in Australian Aboriginal populations) as retained plesiomorphies and argue that these traits cannot be used to show continuity (Lieberman 2000). In response, many multiregionalists have revised their position to suggest that the reduction of the browridge in later Neandertals, such as St Césaire and Vindija, represents a synapomorphy between Neandertals and modern humans, likely due to interbreeding. The underlying assumption here is that these robust traits have a strong genetic component. Furthermore, there is a notable decrease in cranial robusticity from the early Upper Palaeolithic to late Upper Palaeolithic. It has been suggested that this may reflect changes in diet. Transition from hunter-gather to agricultural lifestyle is associated with a reduction in cranial robusticity, although correlation does not necessarily prove causation. However, not all hunter-gather groups are universally more robust than argriculturalists, which might suggest some other factors at play.

A recent in press paper by Baab et al. sets out to examine the possible mechanisms behind robust cranial characters. The null hypothesis in their study is that neutral evolutionary processes (e.g. genetic drift) were responsible for the pattern of cranial robusticity in modern humans - the rejection of which would suggest selection acting on these traits. To test the null hypothesis of neutral evolution of cranial robusticity Mahalonobis D2 distances for robust characters were compared to Ddm distances derived from microsatellite data. Microsatellites are useful in reconstructing evolutionary relationships due to their unusually high mutation rates, which result in largely selectively neutral polymorphisms.

Of the variables examined, only cranial shape was significantly correlated with robusticity, while cranial size, climate and neutral genetic distances were not. This is at odds with an earlier study by Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996) (1996) who found the strongest correlation between cranial robusticity and cranial size. This finding may be due to use of geometric morphometrics by Baab and colleagues, which is better at separating size and shape compared to the linear morphometrics used by Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996).

Cranial robusticity was not correlated with neutral genetic distances, suggesting that neutral evolutionary processes (e.g. genetic drift) were not responsible for the pattern of cranial robusticity in the populations studied. As noted by the authors, this finding could also be explained by a non-perfect match of populations among some of the cranial and molecular samples. In studies such as this one, it is often difficult to find an exact match between the populations from which we derive our cranial and molecular data. In such cases, we are left with the choice of eliminating samples or using another genetically similar population. The authors choose the latter but neither option is ideal and both have their own disadvantages. Unfortunately, the reason for including Upper Palaeolithic and Neolithic samples in this study is never fully explained and the assumption that modern genetic populations are appropriate proxies for such populations is never justified. Setting this aside, the findings of this study caution the use of robust traits in constructing phylogenetic relationships in modern humans.

The strongest correlations were found between cranial robusticity and either cranial or masticatory shape. This lends support to the hypothesis that robusticity is in some part functionally determined. The study also found crania with more prognathic faces, longer skulls, expanded glabellar and occipital regions to be more robust. Mirazón Lahr and Wright (1996) noted a similar tendency of longer skulls to have superstructures, while further emphasising their tendency to be associated with narrow skulls and a large palatal region.

While most of the robust variables in this study were areas of muscle insertions, the supraorbital region has a distinct aetiology. While many have interpreted the supraorbital region as an area of stress reinforcement in the skull (the so-called beam model) which is strongly influenced by mastication (Endo 1966, 1970; Russell 1985), there is a strong evidence to suggest that this is not its primary purpose. Supraorbital development begins early in life, suggesting that the supraorbital ridge may be part of the overall craniofacial complex and is likely under genetic control. While the beam model is intuitive, it is unsupported by empirical data. Hylander and colleagues (Hylander et al. 1991a, 1991b, 1992; Hylander and Ravosa 1992) conducted in vivo strain gauge experiments in different primates to assess the amount of strain magnitudes generated during mastication. They found these levels to be low to induce bone deposition in all the species they studied, even when chewing hard food. Moreover, anthropoids do not show a correlation between the browridge and the moment arms of the masticatory muscles, as the beam model would predict (Ravosa 1991). These researchers adopt the model proposed by Moss and Young (1960), which views supraorbital development as the result of placement of the brain and eyes. They postulated that the reduction of the brow ridge in modern humans was related to the expansion of the frontal lobe in our species. In hominins with orbits positioned well in front of the frontal lobes, as in chimpanzees or the erectines, the space between the orbits and the brain case is bridged by a brow ridge. If the supraorbital region is under genetic control, as the research of Hylander and Ravosa suggests, it would be of interest to examine this region in isolation to assess if it correlates with neutral evolutionary processes, particularly in light of a recent paper by Von Cramen-Taubedal which found the shape of the frontal bone to be consistent with neutral genetic expectation.

References

Baab KL, SE Freidline, SL Wang, T Hanson. 2009. Relationship of cranial robusticity to cranial form, geography and climate in Homo sapiens (in press). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

Curnoe D. 2009. Possible causes and significance of cranial robusticity among Pleistocene-Early Holocene Australians. Journal of Archaeological Science (2009) vol. 36 (4): 980-990.

Endo B. 1966. Experimental studies on the mechanical significance of the form of the human facial skeleton. J Faculty Sci Univ Tokyo (Section V, Anthropol) 3:1–106.

Endo B. 1970. Analysis of stress around the orbit due to masseter and temporalis muscles respectively. J Anthropol Soc Nippon 78:251–266.

Frayer DW, MH Wolpoff, AG Thorne, FH Smith, GG Pope. Theories of modern human origins: the paleontological test. American Anthropologist (1993) vol. 95 (1): 14-50.

Hylander WL, Picq PG, Johnson KR. 1991a. Masticatory–stress hypotheses and the supraorbital region of primates. Am J Phys Anthropol 86:1–36.

Hylander WL, Picq PG, Johnson KR. 1991b. Function of the supraorbital region of primates. Arch Oral Biol 36:273– 281.

Hylander WL, Ravosa MJ. 1992. An analysis of the supraorbital region of primates: a morphometric and experimental approach. In: Smith P, Tchernov E,

editors. Structure, function and evolution of teeth. Tel Aviv: Freund Publishing. p 223–255.

Lieberman, DE. (2000) Ontogeny, homology, and phylogeny in the Hominid craniofacial skeleton: the problem of the browridge. In P. O'Higgins and M. Cohn (eds.) Development, Growth and Evolution: implications for the study of hominid skeletal evolution. London: Academic Press, pp. 85-122.

Moss ML, RW Young. 1960. A functional approach to craniology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 18:281-292.

Mirazón Lahr M, RVS Wright. 1996. The question of robusticity and the relationship between cranial size and shape in Homo sapiens. Journal of Human Evolution.

Ravosa MJ. 1991. Interspecific perspective on mechanical and nonmechanical models of primate circumorbital morphology. Am J Phys Anthropol. 86(3):369-96.

Russell MD. 1985. The Supraorbital Torus:" A Most Remarkable Peculiarity". Current Anthropology. vol. 26 (3) pp. 337

Wolpoff MH, J Hawks, DW Frayer, K Hunley. 2001. Modern Human Ancestry at the Peripheries: A Test of the Replacement Theory. Science. vol. 291 (5502):293-297.

Above photo modified from original by Thomas Hawk under creative commons license.