Irish Neandertals!

Thu, Dec 3 2009 01:23 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

This abstract from a 1961 paper made me smile:

Casey AE, Franklin RB. 1961. Cork-kerry Irish compared anthropometrically with 139 modern and ancient peoples. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 36 (9).

Living Cork-Kerry Irish were compared with 139 modern and ancient peoples using 36 factors, 14 blood groups, 3 skin, hair and eye pigmentations and 22 physical measurements. The method was a form of multiple correlation in which the class interval for each factor was one-half the standard deviation, and numerical values allocated to each half-standard deviation. The Irish, Northern Scots, Icelanders, S.W. Norse, N. Dutch and Frisians form a racial entity with 97 per cent. inter-correlation and very little change during the past 1,000–4,000 years. There is a high correlation with the ancient Scythians substantiating the Irish legends of descent from the kings of Scythia. There is a substantial mixture of upper palaeolithic and Neanderthal man in the north-western perimeter of Europe, exemplified by the people of Cork and Kerry, a mixture not shared by the American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, and by the Bushmen and Pygmies of Africa. There is a good possibility that the large frame, red hair, blue eyes and white skin of West Europe was contributed by upper palaeolithic and Neanderthal men.

Casey AE, Franklin RB. 1961. Cork-kerry Irish compared anthropometrically with 139 modern and ancient peoples. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 36 (9).

View Comments

One chin does not a modern human make

Sat, Nov 21 2009 01:04 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

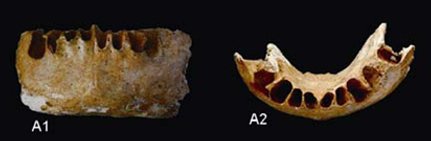

Chinese scientists say that a recently discovered partial jaw from Guangxi challenges the ‘out of Africa’ model of modern human origins, while lending support to the multiregional hypothesis. The 110,000 year-old mandible is described as having a chin that juts “ever so slightly outward.” These scientists assert that the presence of chin shows that there was significant gene flow between populations of modern Homo sapiens and archaic Homo.

Wu Xinzhi of the Chinese Academy of Sciences had the following to say about the find:

”The finding was strong evidence to prove the multiregional model, and from this evidence, it was significant to solve the academic dispute between 'the multiregional mode' and 'out of Africa theory’”.

It is interesting to note Xinzhi’s use of the past simple tense to suggest that this is a closed case. Far from it! Palaeoanthropological theory has moved on from the multiregional sensu stricto versus ‘out of Africa’ sensu stricto dichotomy that predominated the discussion during the latter half of the last century. Nevertheless, the question of how much gene flow, if any, took place between modern and archaic Homo is still very much a debated issue.At this stage you may be wondering why there has been such furore over a chinned jaw. As long ago as 1775, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach commented on the uniqueness of the modern human chin:

In the animals there is scarcely a particular chin which can be considered as comparable to that of man: and in those men who, as is often said, seem to have something apish in their countenance, this generally resides in a deeply-retreated chin.

The distinctive modern human chin develops through the combination of bone deposition on the inferior part of the jaw and resorption around the alveolar region. In other primates the entire jaw undergoes deposition. The modern human chin is characterised as having a central keel, with hollowed out depressions (known as mental fossae) to either side, together with a protruding inferior portion. This distended mental protuberance and lateral extremities make up the mental trigone, giving the chin the appearance of an inverted T. It is the combination of all these anatomical features that make up the prototypal modern chin. However, chins show great variability, with some modern humans not having any.This variability is also extends to earlier hominins. The Middle Pleistocene fossils from the Sima de los Huesos have been described as having chins, and even well-developed mental trigones. Among Pleistocene hominins, Neandertals appear to have the most divergent pattern from the modern configuration, universally lacking the inverted T and mental fossae. While it has been argued that the Neandertal mandibles from the Croatian site of Vindija show the development of incipient chins, this has not been borne out by later analyses.

Some of the ‘modern’ Klasies River Mouth mandibles do not have developed mental trigones, midline keel or a thickening of the inferior margin. However, the modern designation of this material is controversial with these fossils showing a mosaic of both archaic and modern features. Similarly, the modern humans from Qafzeh show variable expression of the inverted T and mental fossae, with no indication of these features in the Skhūl specimens. The 700-800,000 year-old Tighenif mandibles show a surprisingly modern configuration complete with central keel, a thickened inferior portion, and the development of a triangular protuberance. The presence of a chin in these specimens could represent a synapomorphy with modern humans.

Based on the archaeological record, it appears that modern humans left Africa some time around 100,000 years ago. Among the oldest undisputed modern human remains in China come from Zhoukoudian Cave at around 35,000 years BP. The possibly earlier fossil from Liujiang is marred with dating problems. In order for the Chinese scientists’ assertion to hold, it would require an even earlier exit from Africa or expansive gene flow between modern humans living in Africa and archaic humans in Asia; claims for which the evidence is currently lacking. Future analyses of the specimens will determine whether these chins have a truly modern form or whether the pattern is more like the non-homologous protruding inferior jaws seen in other archaic specimens. Alternatively, if these specimens end up being the result of convergent evolution it would raise questions about the functional significance of a chin. Finally, if these fossils show a pattern similar to the one seen in the Tighenif fossils it may suggest that they belong to the same clade.

References and further reading

Ahern JC (1993). The Transitional Nature of the Late Neandertal Mandibles from Vindija Cave, Croatia. M.A. thesis. Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University.

Blumenbach, JF (1978). The anthropological treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach / translated and edited from the Latin, German, and French originals by Thomas Bendyshe. Boston : Longwood Press.

Hawks, J (2009). It came from Guangxi.

McKenna, P (2009). Chinese challenge to 'out of Africa' theory. New Scientist.

Rosas, A. (1995). Seventeen new mandibular specimens from the Atapuerca/Ibeas Middle Pleistocene hominids sample. J. hum. Evol. 28, 533–559.

Schwartz JH, Tattersall I (2000). The human chin revisited: what is it and who has it? J Hum Evol 38:367-409.

Schwartz JH, Tattersall I (2002) The Human Fossil Record, Vol. 1: Craniodental Morphology of Genus Homo (Europe) Wiley-Liss: New York.

Stone R (2009). Signs of Early Homo sapiens in China? Science 326 (5953) p 655.

Above image: Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Full frontal hominins

Thu, Nov 5 2009 01:43 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

One of the most visually striking differences between modern humans and other hominins is the shape of the forehead. The frontal bone of the forehead serves two primary functions: it houses the frontal lobes of the brain in the anterior cranial fossa and also forms the orbital roof. When the orbits are positioned anterior to the frontal lobes, a supraorbital torus or brow ridge, forms in order to bridge the gap. This is particularly the case in archaic members of the genus Homo, whose brain cases are positioned well behind their faces.

The incredible brow ridges of Homo erectus is perhaps this species most salient physical feature. They possess a flattened forehead with a bar-like brow ridge over the eye sockets. The supraorbital torus is continuous and thickened laterally, which in turn is associated with a pinching of the orbital breadth behind the eye sockets, known as postorbital constriction. In H. erectus, the supraorbital torus is separated from the frontal squama by a depression called the posttoral sulcus. While most Erectines conform to this general bauplan, there is a lot of regional variation in the exact form of the torus.

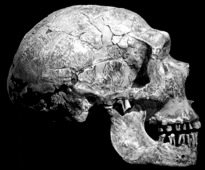

Neandertals are characterised by their long, large, low and wide skull. They have a double-arched browridge above the orbits, which angles backward on the sides of the face. It is depressed along the middle by the presence of a supraglabellar fossa. Compared to H. erectus, Neandertals have a more vertical and rounded forehead, with a less pronounced supraorbital torus.

Modern humans have a vertical forehead, due to in no small part to the expansion of the front part of the brain. Unlike in other hominins, the frontal lobes sit directly above the orbits, negating the need for a supraorbital torus. Instead, we tend to have relatively lightly developed superciliary arches. In present day populations, large supraorbitals are generally seen in individuals that have both robust and narrow skulls. Supraorbital ridges can also occur in cases of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as microcephaly, in which case normal orbital size is combined with smaller cerebral size. The presence of a supraorbital torus in the hominin Homo floresiensis was one of the traits that some researchers used to suggest that these dwarf humans were in fact microcephalic Homo sapiens.

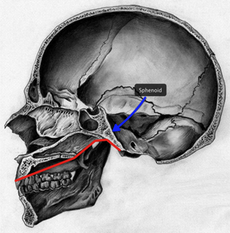

Modern adult humans have the most flexed basicranium of any mammal. This is due largely to us having a more vertically oriented sphenoid bone. A more flexed cranial base repositions the face directly below the anterior cranial fossa, while a more extended cranial base results in greater facial prognathism. In turn, the combination of an extended cranial base and facial forwardness influences the development of the supraorbital region. Early modern human skulls, such as Skhūl V and Dar es-Soltan, have prominent brow ridges. The development of large supraorbitals in these specimens results from greater cranial base angulation. In this regard, the development of the supraorbital region in some early modern humans does not result from neuro-orbital disjunction like in archaic humans, but primarily because of their more extended cranial base.

While much has been written about the non-metric variation of the frontal in hominins, there is little in the way of metric analyses, due to the bone's lack of cranial landmarks. Sheela Athreya recently carried out a quantitative study of the frontal bones of various Pleistocene hominins. She collected outlines along the sagittal and parasagittal planes of the bone. Based on her analyses, specimens were classified as either Early Pleistocene, Homo erectus, Middle Pleistocene, Neandertal or anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

The highest classification accuracy was along the midsagittal plane, with a success rate of a mere 68%. In other words, using this technique almost one-third of specimens were misclassified. A well-seasoned palaeoanthropologist would have a much higher success rate using only non-metric traits. The key to identifying which species a particular frontal bone comes from involves looking at the totality of features along the entire length of the torus and surrounding bone. It is likely that if each of the curves were combined in a multivariate analysis they would have yielded a much higher classificatory success rate. Linear measurements along a curve only capture two dimensions of the frontal form, thereby losing a lot of information contained in the third dimension. A better approach would be to digitise a three-dimensional dense point cloud along the entire bone and to analyse the region using geometric morphometrics. However, such equipment is expensive and not available in most anthropology departments.

Perhaps the most important outcome of this study was that it quantitatively confirmed some of the general characteristics of the frontal form of Homo, that have been previously described qualitatively. These include the fact that most of the variation in the frontal bone between Pleistocene groups is along the midsagittal plane. The study additionally found Homo erectus to differ from all other groups in the projection of the glabellar region. Finally, it identified modern humans as differing from all other groups in the curvature of the forehead, as well as the prominence of the lateral supraorbital torus. This confirms what many palaeoanthropologists have been saying for a long time – the lack of a supraorbital torus in modern humans is a uniquely derived feature.

References

Athreya, S. A comparative study of frontal bone morphology among Pleistocene hominin fossil groups, J Hum Evol (2009), doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.09.003.

Lahr, MM. The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity : A Study on Cranial Variation . Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Lieberman, Daniel E, Osbjorn M Pearson, and Kenneth M Mowbray. "Basicranial Influence on Overall Cranial Shape." Journal of Human Evolution 38 (2000): doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0335.

Martin RD, MacLarnon AM, Phillips JL, Dussebieux L, Williams PR, Dobyns WV. 2006a. Comment on ‘‘The brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis.’’ Science 312:999b.

Trinkaus. Modern Human versus Neandertal Evolutionary Distinctiveness. Current Anthropology (2006) vol. 47 (4) pp. 597-620.

Trinkaus. European early modern humans and the fate of the Neandertals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2007) 104 (18) pp. 7367-7372.

Above photos modified from originals by missmareck and arnybo under creative commons license.

Image of lateral dissected skull by dollinjune14, via deviantART (modified from original).

The incredible brow ridges of Homo erectus is perhaps this species most salient physical feature. They possess a flattened forehead with a bar-like brow ridge over the eye sockets. The supraorbital torus is continuous and thickened laterally, which in turn is associated with a pinching of the orbital breadth behind the eye sockets, known as postorbital constriction. In H. erectus, the supraorbital torus is separated from the frontal squama by a depression called the posttoral sulcus. While most Erectines conform to this general bauplan, there is a lot of regional variation in the exact form of the torus.

Neandertals are characterised by their long, large, low and wide skull. They have a double-arched browridge above the orbits, which angles backward on the sides of the face. It is depressed along the middle by the presence of a supraglabellar fossa. Compared to H. erectus, Neandertals have a more vertical and rounded forehead, with a less pronounced supraorbital torus.

Modern humans have a vertical forehead, due to in no small part to the expansion of the front part of the brain. Unlike in other hominins, the frontal lobes sit directly above the orbits, negating the need for a supraorbital torus. Instead, we tend to have relatively lightly developed superciliary arches. In present day populations, large supraorbitals are generally seen in individuals that have both robust and narrow skulls. Supraorbital ridges can also occur in cases of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as microcephaly, in which case normal orbital size is combined with smaller cerebral size. The presence of a supraorbital torus in the hominin Homo floresiensis was one of the traits that some researchers used to suggest that these dwarf humans were in fact microcephalic Homo sapiens.

Modern adult humans have the most flexed basicranium of any mammal. This is due largely to us having a more vertically oriented sphenoid bone. A more flexed cranial base repositions the face directly below the anterior cranial fossa, while a more extended cranial base results in greater facial prognathism. In turn, the combination of an extended cranial base and facial forwardness influences the development of the supraorbital region. Early modern human skulls, such as Skhūl V and Dar es-Soltan, have prominent brow ridges. The development of large supraorbitals in these specimens results from greater cranial base angulation. In this regard, the development of the supraorbital region in some early modern humans does not result from neuro-orbital disjunction like in archaic humans, but primarily because of their more extended cranial base.

While much has been written about the non-metric variation of the frontal in hominins, there is little in the way of metric analyses, due to the bone's lack of cranial landmarks. Sheela Athreya recently carried out a quantitative study of the frontal bones of various Pleistocene hominins. She collected outlines along the sagittal and parasagittal planes of the bone. Based on her analyses, specimens were classified as either Early Pleistocene, Homo erectus, Middle Pleistocene, Neandertal or anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

The highest classification accuracy was along the midsagittal plane, with a success rate of a mere 68%. In other words, using this technique almost one-third of specimens were misclassified. A well-seasoned palaeoanthropologist would have a much higher success rate using only non-metric traits. The key to identifying which species a particular frontal bone comes from involves looking at the totality of features along the entire length of the torus and surrounding bone. It is likely that if each of the curves were combined in a multivariate analysis they would have yielded a much higher classificatory success rate. Linear measurements along a curve only capture two dimensions of the frontal form, thereby losing a lot of information contained in the third dimension. A better approach would be to digitise a three-dimensional dense point cloud along the entire bone and to analyse the region using geometric morphometrics. However, such equipment is expensive and not available in most anthropology departments.

Perhaps the most important outcome of this study was that it quantitatively confirmed some of the general characteristics of the frontal form of Homo, that have been previously described qualitatively. These include the fact that most of the variation in the frontal bone between Pleistocene groups is along the midsagittal plane. The study additionally found Homo erectus to differ from all other groups in the projection of the glabellar region. Finally, it identified modern humans as differing from all other groups in the curvature of the forehead, as well as the prominence of the lateral supraorbital torus. This confirms what many palaeoanthropologists have been saying for a long time – the lack of a supraorbital torus in modern humans is a uniquely derived feature.

References

Athreya, S. A comparative study of frontal bone morphology among Pleistocene hominin fossil groups, J Hum Evol (2009), doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.09.003.

Lahr, MM. The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity : A Study on Cranial Variation . Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Lieberman, Daniel E, Osbjorn M Pearson, and Kenneth M Mowbray. "Basicranial Influence on Overall Cranial Shape." Journal of Human Evolution 38 (2000): doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0335.

Martin RD, MacLarnon AM, Phillips JL, Dussebieux L, Williams PR, Dobyns WV. 2006a. Comment on ‘‘The brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis.’’ Science 312:999b.

Trinkaus. Modern Human versus Neandertal Evolutionary Distinctiveness. Current Anthropology (2006) vol. 47 (4) pp. 597-620.

Trinkaus. European early modern humans and the fate of the Neandertals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2007) 104 (18) pp. 7367-7372.

Above photos modified from originals by missmareck and arnybo under creative commons license.

Image of lateral dissected skull by dollinjune14, via deviantART (modified from original).

Did Neandertals and modern humans interbreed?

Tue, Oct 27 2009 11:36 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

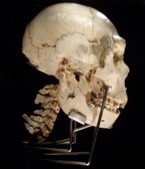

Ever since William King proposed the taxonomic designation Homo neanderthalensis in 1864, there has been intense debate as to whether Neandertals represent a distinct species from us. Species, as defined by the biological species concept, are populations of organisms that can potentially interbreed and have fertile offspring. It is believed that the lineage leading to Neandertals and modern humans split sometime around 500,000 years ago. For most of their existence Neandertals and early modern humans were geographically isolated (and by extension reproductively isolated) from one another. The big question is whether they could have produced viable offspring when they met.

Today, most researchers acknowledge that some sexual encounters could have occurred between Neandertals and modern humans. The more interesting question is how common were these encounters and did they leave their mark on the modern gene pool. Undoubtedly, modern humans and Neandertals would have recognised each other as fellow humans but this does not mean that they would have acted humanely to each another. Countless social and psychological studies have shown humans to have a very strong "us versus them" mentality, that no doubt also existed in our ancestors. It is unlikely that modern humans and Neandertals had an easy relationship. Most sexual encounters that took place between the two were likely opportunistic and probably involved enslavement and rape.

The morphological evidence

Palaeoanthropologists generally have little problem seperating Neandertals and modern humans based on their gross morphologies. However, some of the earliest modern humans from central Europe have traits that have been seen as evidence for continuity between them and Neandertals. These fossils, particularly those from Peştera cu Oase in Romania and Mladeč in the Czech Republic, have been touted as exemplars for modern-Neandertal admixture. These specimens show traits that are seen in high frequencies in Neandertals, such as bunning of the occipital and the presence of a suprainiac fossa.

However, many researchers have questioned whether these traits are in fact distinctly Neandertal. For instance, the form of the occipital seems to be different in early Upper Palaeolithic populations, leading many to favour the term hemibun to describe the shape of the occipital in early Europeans. Lieberman and colleagues has gone as far as to suggest that the buns seen in these two groups are not homologous. Similarly, it has been argued that the shape of the suprainiac fossa is distinct in early modern Europeans compared to Neandertals.

A palpable difficulty in assessing proposed Neandertal traits in early modern humans is that both groups shared similar niches and some traits may be the result of lifetime behavioural adaptations or convergent evolution. Indeed, the shared robustness of these early humans is likely due to the higher physical activities of these Late Pleistocene groups than during later period.

The genetic evidence

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has some characteristics that make it ideal for analyses of ancient specimens. MtDNA is found in abundance – cells can have thousands of copies of mtDNA, while only containing two copies of nuclear DNA. Moreover, its structure and location within the cell make it more resistant to decay. All the studies of Neandertal mtDNA to date cluster outside the range for modern human mtDNA variation. However, the mitochondria contain only a small part of the total DNA that make up a genome. The possibility that Neandertal genes could show up somewhere else in the genome cannot be ruled out.

The recent announcement by Svante Pääbo that he is sure that Neandertals and modern humans had sex is quite a bold pronouncement coming from a scientist. It raises the question of whether this ascertain is based on some hard evidence they found while sequencing the Neandertal genome. It is possible that if there was some Neandertal genes passed on to the first moderns in Europe, they could have got eliminated from the subsequent gene pool as population sizes fluctuated during the more severe climatic episodes. A more likely scenario is that Pääbo's team found evidence of modern introgression in the Neandertal genome. In all likelihood the incoming modern humans were more numerous than the Neandertals, thereby absorbing the endemic populations through genetic swamping.

References

Caspari RE. 1991. The evolution of the posterior cranial vault in the central European Upper Pleistocene. PhD dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

King, W., 1864. The reputed fossil man of Neanderthal. Quarterly Journal of Science 1, 88–97.

Krings et al. 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell vol. 90 (1) pp. 19-30.

Krings M, Capelli C, Tschentscher F, et al. 2000. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nat Genet 26, 144–146.

Lieberman et al. 2000. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. Evol. vol. 38 (2) pp. 291-315.

Nara MT. 1994. Etude de la variabilité de certainscaractères métriques et morphologiques des Néandertaliens. Bordeaux: Thèse de Docteur.

Pääbo S, Poinar H, Serre D, et al. 2004. Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Ann Rev Genet 38, 645–679.

Above photos modified from originals by erix! and fangleman under creative commons license.

Today, most researchers acknowledge that some sexual encounters could have occurred between Neandertals and modern humans. The more interesting question is how common were these encounters and did they leave their mark on the modern gene pool. Undoubtedly, modern humans and Neandertals would have recognised each other as fellow humans but this does not mean that they would have acted humanely to each another. Countless social and psychological studies have shown humans to have a very strong "us versus them" mentality, that no doubt also existed in our ancestors. It is unlikely that modern humans and Neandertals had an easy relationship. Most sexual encounters that took place between the two were likely opportunistic and probably involved enslavement and rape.

The morphological evidence

Palaeoanthropologists generally have little problem seperating Neandertals and modern humans based on their gross morphologies. However, some of the earliest modern humans from central Europe have traits that have been seen as evidence for continuity between them and Neandertals. These fossils, particularly those from Peştera cu Oase in Romania and Mladeč in the Czech Republic, have been touted as exemplars for modern-Neandertal admixture. These specimens show traits that are seen in high frequencies in Neandertals, such as bunning of the occipital and the presence of a suprainiac fossa.

However, many researchers have questioned whether these traits are in fact distinctly Neandertal. For instance, the form of the occipital seems to be different in early Upper Palaeolithic populations, leading many to favour the term hemibun to describe the shape of the occipital in early Europeans. Lieberman and colleagues has gone as far as to suggest that the buns seen in these two groups are not homologous. Similarly, it has been argued that the shape of the suprainiac fossa is distinct in early modern Europeans compared to Neandertals.

A palpable difficulty in assessing proposed Neandertal traits in early modern humans is that both groups shared similar niches and some traits may be the result of lifetime behavioural adaptations or convergent evolution. Indeed, the shared robustness of these early humans is likely due to the higher physical activities of these Late Pleistocene groups than during later period.

The genetic evidence

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has some characteristics that make it ideal for analyses of ancient specimens. MtDNA is found in abundance – cells can have thousands of copies of mtDNA, while only containing two copies of nuclear DNA. Moreover, its structure and location within the cell make it more resistant to decay. All the studies of Neandertal mtDNA to date cluster outside the range for modern human mtDNA variation. However, the mitochondria contain only a small part of the total DNA that make up a genome. The possibility that Neandertal genes could show up somewhere else in the genome cannot be ruled out.

The recent announcement by Svante Pääbo that he is sure that Neandertals and modern humans had sex is quite a bold pronouncement coming from a scientist. It raises the question of whether this ascertain is based on some hard evidence they found while sequencing the Neandertal genome. It is possible that if there was some Neandertal genes passed on to the first moderns in Europe, they could have got eliminated from the subsequent gene pool as population sizes fluctuated during the more severe climatic episodes. A more likely scenario is that Pääbo's team found evidence of modern introgression in the Neandertal genome. In all likelihood the incoming modern humans were more numerous than the Neandertals, thereby absorbing the endemic populations through genetic swamping.

References

Caspari RE. 1991. The evolution of the posterior cranial vault in the central European Upper Pleistocene. PhD dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

King, W., 1864. The reputed fossil man of Neanderthal. Quarterly Journal of Science 1, 88–97.

Krings et al. 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell vol. 90 (1) pp. 19-30.

Krings M, Capelli C, Tschentscher F, et al. 2000. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nat Genet 26, 144–146.

Lieberman et al. 2000. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. Evol. vol. 38 (2) pp. 291-315.

Nara MT. 1994. Etude de la variabilité de certainscaractères métriques et morphologiques des Néandertaliens. Bordeaux: Thèse de Docteur.

Pääbo S, Poinar H, Serre D, et al. 2004. Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Ann Rev Genet 38, 645–679.

Above photos modified from originals by erix! and fangleman under creative commons license.

John Hawks on Ardipithecus

Razib Khan of the Gene Expression blog interviews John Hawks regarding the significance of Ardipithecus ramidus.

Homo heidelbergensis and the muddle in the middle

Sat, Oct 10 2009 11:45 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

At the conference, much attention was focused on the Middle Pleistocene "muddle in the middle" [3], particularly the role of Homo heidelbergensis in hominin evolution. While H. heidelbergensis possesses both archaic and derived traits intermediate between H. erectus and later members of the Homo genus, it lacks uniquely derived traits or autapomorphies, which are a prerequisite for defining a species.

H. heidelbergensis has traits that have been interpreted as nascent Neandertal autapomorphies, leading some researchers to propose that there was a continuous evolution of Neandertals [4-6]. This accretion model would make H. heidelbergensis a chronospecies on the continuum of the Neandertal lineage, a view championed by Jean-Jacques Hublin. The accretion model proposes that Neandertals evolved by anagenesis, i.e. non-branching evolutionary change.

Another scenario views both the European and African H. heidelbergensis as a single species, and the last common ancestor of both Neandertals and modern humans. Alternatively, H. heidelbergensis could have become isolated in Europe and evolved into Neandertals, while the African populations led to modern humans.

During the conference, Ian Tattersall noted that while the accretion model explains some of the variation in the Middle Pleistocene, it cannot account for some outliers, such as the 28 or so specimens that have been recovered from the Sima de los Huesos in Atapuerca, Spain. Tattersall is not the first author to call the accretion model into question [7]. Recent dates have placed the Sima fossils at just over half-a-million years old. Based on the dissimilarity between these fossils and the penicontemporaneous H. heidelbergensis from the rest of Europe, Tattersall proposes that two hominin lineages coexisted in Europe before the arrival of H. sapiens. He suggests that one line (which may include the Sima specimens) led to the Neandertals, while the branch which included H. heidelbergensis went extinct. If Tattersall is correct it would mean that the Sima fossils, which are currently classified as H. heidelbergensis, must be designated another name.

Hublin is to his guns and doesn't see any need to reclassify the Sima material. He goes as far as to suggest binning the species name H. heidelbergensis altogether and instead reassigning all these Middle Pleistocene fossils as H. neanderthalensis. Whatever the outcome is in this debate, it appears that hominin evolution in the Middle Pleistocene is more complex than we have previously suspected.

References

1. Balter M. New work may complicate history of Neandertals and H. sapiens. Science 2009; 326:224-5.

2. Darwin C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. New York, A. L. Burt; 1874.

3. Butzer KW, Isaac GL, International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences 9C1. After the Australopithecines : stratigraphy, ecology, and culture, change in the Middle Pleistocene . The Hague : Mouton ; Chicago : distributed in the USA and Canada by Aldine; 1976.

4. Hublin. Paleogeography, and the evolution of the Neandertals. In: Akazawa, Aoki, Bar-Yosef, Eds. Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:295-310.

5. Hublin. Climatic Changes, Paleogeography, and the Evolution of the Neandertals. In: Akazawa, Aoki, Bar-Yosef, Eds. Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:295-310.

6. Martinón-Torres M, Bastir M, Bermúdez de Castro JM, Gómez A, Sarmiento S, Muela A, Arsuaga JL. Hominin lower second premolar morphology: evolutionary inferences through geometric morphometric analysis. J Hum Evol 2006; 50:523-33.

7. Hawks JD, Wolpoff MH. The accretion model of Neandertal evolution. Evolution 2001; 55:1474-85.

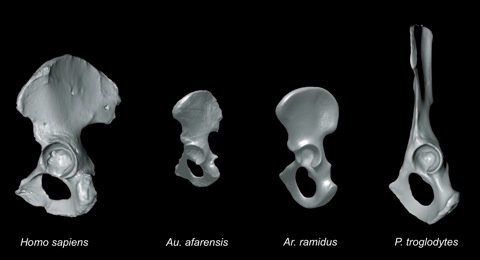

The pelvis of Ardipithecus ramidus

Fri, Oct 2 2009 06:04 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

One of the anatomical features that sets humans apart from other living primates is the shape of our pelvis. The shift from a quadrupedal aboreal lifestyle to habitually walking on two legs requires a substantial reconfiguration of the hip region. The 4.4 million year old Ardipithecus ramidus fossil remains give us a glimpse of what the one of the earliest members of the hominin lineage looked like. While the feet of Ar. ramidus show that it was still adapted to life in the trees, the pelvis shows significant adaptations to walking upright on two legs.

The gluteus maximus, which is a relatively minor muscle in quadrupeds has been reconfigured into the largest muscle in humans, in order to stabilize the pelvis and trunk in an upright position. The derived nature of the ilium of Ar. ramidus suggests that the enlargement of the gluteal maximus had already begun. The craniocaudal height of the pelvis is also reduced, which would have lowered the relatively long trunk's centre of mass. This would have allowed for more stable bipedal locomotion.

However, the ischium is quite primitive compared to the ilia, likely to accommodate the large hindlimb musculature required for tree climbing. The two best preserved australopithicine pelves, AL 288-1 and Sts 14, both have short ischia, like those seen in modern humans. The preserved portion of the ischial ramus in Ar. ramidus is significantly larger than that found in any of the Australopithecines. A long ischium creates a greater moment arm suggesting that Ar. ramidus had relatively powerful hamstrings, a trait that is common in tree-dwelling primates.

The configuration of the ARA-VP-6/500 pelvis suggests that lower lumbars were probably posteriorly positioned, allowing for lordosis of the spine. A reduction in iliac height would have further facilitated lordosis. Lordosis positions the spine to a more forward position, so that it directly overlies the hips during erect posture. Lower spinal lordosis would have allowed the full extension of the hips and knee during extended bipedal locomotion.

Ar. ramidus was quite capable of bipedal locomotion, as attested to by the morphology of its pelvis and foot. However, its large thigh muscles and its prehensile big toe show that it was still very much adapted to arboreal life. Ar. ramidus shares arboreal adaptations that were probably present in the human-chimp last common ancestor, as well as bipedal adaptations that are so characteristic of hominins. Ar. ramidus appears to have been an arboreal ape with bipedal adaptations, rather than a biped with arboreal adaptations. It is not until almost half-a-million years later, with the arrival of Australopithecus afarensis, that we find a truly habitual bipedal hominin.

Four Stone Hearth #75

Wed, Sep 9 2009 04:55 | Anthropology | Permalink

Welcome to Four Stone Hearth number 75. Four Stone Hearth is a fortnightly anthropology blog carnival. Topics covered span the four major fields of anthropology: archaeology, socio-cultural anthropology, bio-physical anthropology and linguistic anthropology. If you would like to host the carnival, please write to . The next issue will be hosted at the Afarensis blog on 23 September. So without further preamble, let's get on with the show.

Archaeology

Martin Rundkvist talks about his experience digging at a Middle Neolithic coastal site in Sweden. Among the finds were small potsherds and a fine example of Pitted Ware.

A recent article in the journal Nature reports on the "oldest handaxes" in Europe. John Hawks gives his interpretation regarding the significance of these bifaces, suggesting that although Lower Pleistocene hominins had the technology to produce bifacial handaxes, they were not a necessity.

Biological anthropology

Anybody who has been following anthropology news for the past few weeks will be well aware of the spirited reaction that a recent editorial in Scientific American generated. The article calls for the adoption of more open practices with regard to accessing human fossils. I have written a piece where I give my own take on the issue.

Matthew Wolf-Meyer reviews Jonathan Marks' latest book "Why I am not a scientist". Jonathan Marks is a controversial anthropologist, who sticks to his guns in this, his latest work. Ever thought provoking, Marks is bound to stir up some debate among anthropologists and scientists alike.

There has been a lot of debate regarding whether Central European farmers were the descendants of indigenous hunter-gathers or the result of a demic diffusion from the southeast. Dienkes reports on a new study which suggests that Central European farmers were in fact probably not descended from local hunter-gatherer groups.

Stephen Wang asks the age old question of how similar Neandertals were to us and how they thought about the world.

Linguistic anthropology

The Innovation in Teaching blog explains the concept of a “focused gathering”, a term coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. The post goes on to discuss how this concept helps us better think about classroom dynamics.

Socio-cultural anthropology

Over at Neuroanthropology, Daniel Lende has a revealing piece which looks at food crises in Lesotho and the role funerals play in coping with these food shortages. In another post Daniel takes on the recent "research" by researchers Ogi Ogas and Sai Gaddam, which is plagued by poor methodologies and a pseudoscientific approach to neuroscience. Greg Downey follows this up with his own take on some of the methodological flaws of the investigators, principally their inflexibility in the face of contradictory evidence.

Rex over at the Savage Minds blog suggests that the real question anthropologists should ask regarding internet addiction is not whether it exists but rather "how and in what forms do preexisting cultural structures predispose people to think something is true?"

Greg Laden debunks the fallacy that culture overrides biology. This part of a larger series on the common misperceptions that people have regarding biology.

Idris Mootee thinks that industrial designers need to think like cultural anthropologists. He uses the example of how different cultures adopt their own particular posture while sitting. By being aware of this, designers can better accommodate the needs of the end user. Joana Breidenbach of the Culture Matters blog is of a similar opinion:

"Design thinking has many overlaps with the anthropological approach, such as starting out with as little preconceived ideas about the research topic as possible and gaining an empathetic understanding through immersion during fieldwork."

Lian explores the the archaeology of the worship of Celtic deities in Roman Britain.

Lorenz at the antropologi blog reviews Thomas Hylland Eriksen's new book "Engaging Anthropology". In it, he addresses the question of why anthropologists fail to engage the general public. In a similar piece that appeared in Times Higher Education, anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes asserts that part of the problem may lie with universities:

"Scholars who want to reach diverse publics - through popular writing, speaking or participating in social activism - are not only under-rewarded by their universities, they are often penalised for 'dumbing down' anthropological thinking, cutting social theory into 'soundbites', 'vulgarising' anthropology, sacrificing academic standards or (in the US) for playing to the anti-intellectual, illiberal American popular classes."

Anna Barros shows how trends are subject to selection. She demonstrates how memes can be transmitted from person to person and how they respond to selection pressures.

One more thing…

Each of the four fields of anthropology can offer us a glimpse into our past. Perhaps more importantly, they can take us on a journey and show us the steps which got us to where we are today. Photography offers yet another way of archiving the past. To use the clichéd metaphor – photographs are moments frozen in time. A Flickr photostream by Jason Powell wonderfully bridges the gap between the past and the present, through the medium of photography. Enjoy!

Fossil and data access in palaeoanthropology

Tue, Sep 8 2009 01:50 | Palaeoanthropology | Permalink

A recent article in Scientific American has generated a lot of buzz in the anthropology blogosphere. The piece discusses the problems of accessing human fossil remains, reopening the discussion on how open anthropology needs to be. The reason why data acquisition is such a problem in palaeoanthropology is captured in the opening sentence of an article Stephen Jay Gould and David Pilbeam wrote for Science:

Whenever supply cannot keep up with demand, you can be sure that problems will follow. (Many parents have learned this to their chagrin, when they find out that the Christmas toy du jour, their beloved child so wanted, is sold out.) Each newly unearthed fragment of human bone represents yet another valuable piece in the ever-growing jigsaw puzzle that is our evolutionary history. The study of primary data is of prime importance in paleoanthropology. As a result, a conflict arises, due to the need to study fossils and the limited access placed upon them. Restricted access occurs for a number of reasons, ranging from valid concerns over the fragility of a particular specimen, to scientists reaping the benefits of a research monopoly.

There is an unwritten rule in palaeoanthropology that the discoverers of a fossil have the exclusive rights to publish the initial monograph describing their specimen. Palaeoarchaeologists invest a lot of resources, time and effort in recovering fossils. They will often literally risk body and limb. Dehydration, food poisoning, snake bites, diseases and infections are but some of the hazards field archaeologists face. When they are not digging they are often engaged in the unenviable task of writing grants for their projects. It is understandable that they are wary of outsiders who expect free access to their hard-won prizes.

Ancient fossils usually come out of the ground highly fragmented and in a poor state of preservation. Much time is required to clean, preserve and reconstruct them before conducting a phylogenetic analysis. While many people have focused on the fact that certain specimens have taken an exhorbitant amount of time to describe, thus holding up the process of peer validation, it must also be kept in mind that these represent only a small fraction of the total human fossil record. While it of the utmost importance to make fossils available to outside investigators in a timely fashion, it is perhaps not the most fruitful or constructive area in which to be directing our attention.

Conflicts arise between researchers who want to access fossil material and curators who are genuinely concerned about the wear and tear that these fossils have endured through repeated handling. Curators will often direct researchers to others who have already measured the material in question, to avoid the redundant repetition of measurements. It is often at this point that researchers can come up against a brick wall, with peers who are unwilling to relinquish their valued data. Like the fossils themselves, unique data is a precious commodity and alas is necessary for publication. For good or for ill, peer-reviewed publications are placed in high regard in the anthropological world. Its role when it comes to job-seeking or tenure cannot be underestimated. An incredible amount of data has been collected through the years on ancient human remains but they are rarely put in the public domain. A noteworthy exception is the data on some 3,000 skulls from 17 worldwide populations, measured and made freely available by the eminent anthropologist William W. Howells (pdf file). The Howells' dataset is perhaps that man's most lasting legacy, at least in the sheer number of times his data have been used and referenced. Similarly, we need to place great value on other researchers who make their data available and this should be taken into consideration in matters of career advancement. At a minimum, the sharing of data should be deemed equivalent to research publication.

Positive steps have been taken in the ensure more data is made available. The US National Science Foundation encourage applicants to make provisions to make data available after the research has been completed. The NSF states that:

Anthropologists who fail to comply with these recommendations may have subsequent grant proposals turned down on these grounds. There is an ever-growing number of high quality casts and 3D images of fossils becoming available. Taphonomic processes may deform the fossilised bone and filling in gaps has often required a liberal amount of guesswork. 3D images often allow for better reconstructions of the original specimens, due to the ability to interpolate absent regions and more readily pinpoint and correct deformation. Research centres have woken up to the fact that collaborative projects tend to have a greater synergy due to their symbiotic nature. For palaeoanthropology to become a truly open discipline, it will not only need researchers to be more freehanded with their data, but will require funding agencies, universities and research centres to incentivise such actions.

Related reading

Fossil access editorial @ John Hawks weblog.

Science Suffers From The Idiots At Scientific American @ Anthropology.net.

Take your time @ A Primate of Modern Aspect.

Delson et al. Databases, data access, and data sharing in paleoanthropology: First steps. Evol. Anthropol. (2007) vol. 16 (5).

Gibbons. Glasnost for Hominids: Seeking Access to Fossils. Science (2002) vol. 297 pp. 1464-1468.

Mafart. Human fossils and paleoanthropologists: a complex relation. Journal of Anthropological Sciences (2008) vol. 86 pp. 201-204.

Pilbeam and Gould. Size and Scaling in Human Evolution. Science (1974) vol. 186 ( 4167), 892-901.

Tattersall and Schwartz. Is paleoanthropology science? Naming new fossils and control of access to them. Anat Rec (2002) vol. 269 (6) pp. 239-41.

"Human paleontology shares a peculiar trait with such disparate subjects as theology and extraterrestrial biology: it contains more practitioners than objects for study."

– Stephan J. Gould and David Pilbeam

Whenever supply cannot keep up with demand, you can be sure that problems will follow. (Many parents have learned this to their chagrin, when they find out that the Christmas toy du jour, their beloved child so wanted, is sold out.) Each newly unearthed fragment of human bone represents yet another valuable piece in the ever-growing jigsaw puzzle that is our evolutionary history. The study of primary data is of prime importance in paleoanthropology. As a result, a conflict arises, due to the need to study fossils and the limited access placed upon them. Restricted access occurs for a number of reasons, ranging from valid concerns over the fragility of a particular specimen, to scientists reaping the benefits of a research monopoly.

There is an unwritten rule in palaeoanthropology that the discoverers of a fossil have the exclusive rights to publish the initial monograph describing their specimen. Palaeoarchaeologists invest a lot of resources, time and effort in recovering fossils. They will often literally risk body and limb. Dehydration, food poisoning, snake bites, diseases and infections are but some of the hazards field archaeologists face. When they are not digging they are often engaged in the unenviable task of writing grants for their projects. It is understandable that they are wary of outsiders who expect free access to their hard-won prizes.

Ancient fossils usually come out of the ground highly fragmented and in a poor state of preservation. Much time is required to clean, preserve and reconstruct them before conducting a phylogenetic analysis. While many people have focused on the fact that certain specimens have taken an exhorbitant amount of time to describe, thus holding up the process of peer validation, it must also be kept in mind that these represent only a small fraction of the total human fossil record. While it of the utmost importance to make fossils available to outside investigators in a timely fashion, it is perhaps not the most fruitful or constructive area in which to be directing our attention.

Conflicts arise between researchers who want to access fossil material and curators who are genuinely concerned about the wear and tear that these fossils have endured through repeated handling. Curators will often direct researchers to others who have already measured the material in question, to avoid the redundant repetition of measurements. It is often at this point that researchers can come up against a brick wall, with peers who are unwilling to relinquish their valued data. Like the fossils themselves, unique data is a precious commodity and alas is necessary for publication. For good or for ill, peer-reviewed publications are placed in high regard in the anthropological world. Its role when it comes to job-seeking or tenure cannot be underestimated. An incredible amount of data has been collected through the years on ancient human remains but they are rarely put in the public domain. A noteworthy exception is the data on some 3,000 skulls from 17 worldwide populations, measured and made freely available by the eminent anthropologist William W. Howells (pdf file). The Howells' dataset is perhaps that man's most lasting legacy, at least in the sheer number of times his data have been used and referenced. Similarly, we need to place great value on other researchers who make their data available and this should be taken into consideration in matters of career advancement. At a minimum, the sharing of data should be deemed equivalent to research publication.

Positive steps have been taken in the ensure more data is made available. The US National Science Foundation encourage applicants to make provisions to make data available after the research has been completed. The NSF states that:

It expects investigators to share with other researchers, at no more than incremental cost and within a reasonable time, the data, samples, physical collections and other supporting materials created or gathered in the course of the work.

Anthropologists who fail to comply with these recommendations may have subsequent grant proposals turned down on these grounds. There is an ever-growing number of high quality casts and 3D images of fossils becoming available. Taphonomic processes may deform the fossilised bone and filling in gaps has often required a liberal amount of guesswork. 3D images often allow for better reconstructions of the original specimens, due to the ability to interpolate absent regions and more readily pinpoint and correct deformation. Research centres have woken up to the fact that collaborative projects tend to have a greater synergy due to their symbiotic nature. For palaeoanthropology to become a truly open discipline, it will not only need researchers to be more freehanded with their data, but will require funding agencies, universities and research centres to incentivise such actions.

Related reading

Fossil access editorial @ John Hawks weblog.

Science Suffers From The Idiots At Scientific American @ Anthropology.net.

Take your time @ A Primate of Modern Aspect.

Delson et al. Databases, data access, and data sharing in paleoanthropology: First steps. Evol. Anthropol. (2007) vol. 16 (5).

Gibbons. Glasnost for Hominids: Seeking Access to Fossils. Science (2002) vol. 297 pp. 1464-1468.

Mafart. Human fossils and paleoanthropologists: a complex relation. Journal of Anthropological Sciences (2008) vol. 86 pp. 201-204.

Pilbeam and Gould. Size and Scaling in Human Evolution. Science (1974) vol. 186 ( 4167), 892-901.

Tattersall and Schwartz. Is paleoanthropology science? Naming new fossils and control of access to them. Anat Rec (2002) vol. 269 (6) pp. 239-41.

Above photo by Simon Strandgaard under creative commons license.

Anthro blog carnival: Four Stone Hearth 74

Thu, Aug 27 2009 03:11 | Anthropology | Permalink

The 74th Four Stone Hearth anthropology blog carnival is available over at Adam Henne’s Natures/Cultures blog. Catch up on the latest on anthropology blogging. The next Four Stone Hearth will be hosted here on the 9th of September. Send any anthropology submission for the upcoming carnival to or (be sure to replace [AT] with @ in the email addresses).